Table of Contents

- Introduction to Food waste in India

- Impact of Food Waste in India on Food Security

- A Growing Urban Challenge and Rising Price Pressures

- Environmental Impacts of Food Waste in India

- Stages of Food Loss and Food Waste in India

- Why Later Food Waste Hurts More

- Addressing Food Waste in India

- Conclusion: Combating Food Waste in India for a Sustainable Future

Introduction to Food waste in India

Food waste in India is a growing concern that directly affects the environment and national food security. In a country like India—where millions still go to bed hungry every night—food loss and food waste present a deeply troubling paradox.

While India’s agricultural sector feeds over a billion people, a significant portion of the food produced never reaches anyone’s plate.

These two terms—food loss and food waste—though often used interchangeably, address different parts of the same issue.

Food loss and waste are significant, highly debated topic food loss typically occurs at the early stages of the supply chain—during harvesting, post-harvest handling, storage, and transportation.

In India, this can be due to erratic weather, poor rural infrastructure, lack of cold storage, inadequate market access, or outdated harvesting methods.

For example, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) has reported recurring losses due to storage shortages and pests in government warehouses.

Food waste, on the other hand, occurs at the consumer or retail level. In urban India, this often means leftovers at restaurants, unpurchased stock in supermarkets, or excessive food thrown away at weddings, festivals, and corporate events.

A study by the Indian Institute of Public Administration estimates that nearly 40% of food produced in India is wasted every year—enough to feed over 200 million people.

This massive wastage not only represents a missed opportunity to combat hunger and malnutrition but also imposes a heavy toll on our environment.

As India moves toward becoming a $5 trillion economy, tackling food waste isn’t just a social obligation—it’s an environmental and economic necessity.

Impact of Food Waste in India on Food Security

India faces a stark reality: while it ranks among the top global producers of rice, wheat, fruits, and vegetables, it also houses one of the world’s largest undernourished populations.

According to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) 2023 report, over 224 million people in India are moderately or severely food insecure. In this context, food loss and waste directly undermine national efforts to achieve food security.

As India generates millions of tonnes of food waste each year. Curious about the numbers? See how much food is wasted in India annually.

Food security in India is a complex issue—interwoven with rural poverty, supply chain inefficiencies, inflation, and unequal access to nutritious food.

Every time edible food is lost during transport due to poor logistics, or wasted after a wedding feast, we not only lose calories but also deny nourishment to those in need. This makes food waste not just an economic problem, but a moral one.

The Public Distribution System (PDS) aims to distribute subsidized food to the poor, but its effectiveness is frequently compromised by systemic losses—damaged grain stocks, spoiled pulses, or pilfered rations.

A Growing Urban Challenge and Rising Price Pressures

On the consumer end, rising urban incomes and changing lifestyles have led to more food being wasted at home, in malls, and at events, widening the gap between availability and accessibility.

Moreover, the wastage of food artificially sustains or even inflates prices, especially of perishables. For low-income households—where every rupee counts—this makes it harder to maintain a nutritious and balanced diet. This price sensitivity disproportionately affects women, children, and rural communities.

Reducing food loss along the supply chain—especially at the farm gate and in local mandis—can significantly boost food availability without increasing agricultural inputs or land use.

Here, simple interventions like improved grain storage, access to cold chains, and smarter procurement practices can go a long way in ensuring that food grown in India actually nourishes its people. In developed countries, food banks and recovery systems help bridge the gap between surplus and scarcity.

Food waste in India not only strains environmental resources but also contributes to widespread hunger.

In India, organizations like Reshine Organisation and others working in food redistribution are beginning to play a similar role—rescuing excess food and delivering it to those who need it most. Scaling these efforts nationally can be a game-changer in the fight against hunger.

Environmental Impacts of Food Waste in India

In India, where agriculture supports nearly half of the population, food loss and waste are not just social or economic concerns—they are environmental crises.

Every morsel of wasted food reflects a squandering of precious natural resources that our country can ill afford to lose. From water and land to energy and fossil fuels, the ripple effects of food waste stretch far beyond our plates.

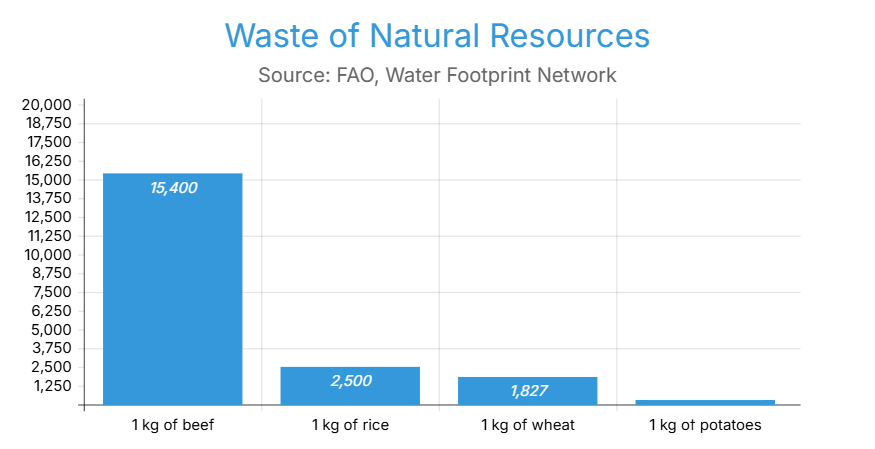

Wastage of Natural Resources

Above chart shows Litres of water wasted vs Amount of Food Wasted

When we throw away food, we are also discarding the vast natural resources that went into producing it. This includes:

1. Water

Agriculture consumes nearly 80% of India’s freshwater resources, and much of this goes into growing crops that never get eaten. Take this into perspective:

- Producing just 1 kg of rice—a staple in Indian households—requires up to 3,000–5,000 litres of water.

- A glass of milk, commonly wasted in urban homes and eateries, represents nearly 1,000 litres of water used in its production.

- Throwing away a chicken curry plate isn’t just about food loss—each kilogram of chicken takes over 4,000–5,500 litres of water to produce.

With increasing water stress across Indian states—Punjab, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Karnataka being especially vulnerable—food waste essentially means pouring our most vital resource down the drain.

2. Land

India has only 2.4% of the world’s land, yet it must feed 17% of the global population.

Overuse of arable land for high-yield farming to meet food demands is already leading to soil degradation, desertification, and biodiversity loss. When food is wasted:

- The cropland used for its cultivation is stressed for no benefit.

- Organic waste dumped in landfills takes up valuable space and produces harmful methane emissions.

- Forests are cleared to create farmland that ends up producing food that may never be consumed.

Studies suggest that globally one-third of agricultural land is used to grow food that is ultimately wasted.

For India, where land disputes, soil exhaustion, and deforestation are mounting issues, this is an unsustainable model.

3. Energy and Fuel

From powering tractors and running irrigation pumps to cold storage and long-distance transport—India’s agri-food system consumes massive amounts of diesel, electricity, and cooking fuel. Wasted food reflects wasted energy at each stage:

- Cold chains, which are critical to prevent spoilage of fruits, vegetables, dairy, and meats, often run on non-renewable energy sources. When the produce is wasted, so is the energy that preserved it.

- Transportation of food—often over long, inefficient routes—adds to fossil fuel usage. Food discarded at cities means fuel was spent for no purpose.

- Cooking food that isn’t consumed wastes cooking gas—particularly significant in rural areas where access to LPG is still being expanded.

Globally, the food system consumes about 30% of the total energy, and India is no exception.

With rising fuel costs and energy scarcity in many regions, minimizing food waste can directly contribute to reducing the country’s carbon footprint.

Contribution to Climate Change

Food waste in India doesn’t just disappear—it ends up in overflowing landfills, where it decomposes and releases methane, a greenhouse gas that is up to 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide in trapping heat.

While methane stays in the atmosphere for a shorter duration (around 12 years), its climate-warming potential is far more aggressive.

Food Waste and India’s Urban Landfills

India generates over 62 million tonnes of municipal solid waste every year, and a significant portion of this—between 40–60%—is organic, mostly comprising food scraps, vegetable peels, leftover meals, and expired perishables.

In cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Kolkata, food waste mountains are piling up in dumpsites like Ghazipur and Deonar, silently contributing to rising local temperatures and toxic air.

Global and National Emissions Impact

Globally, food waste contributes to about 8–10% of all greenhouse gas emissions. If food waste were a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of greenhouse gases after China and the United States.

Though India’s per capita emissions are relatively lower, our overall climate footprint is rising, and food waste is a hidden driver of that increase.

The Methane Problem in Indian Waste Systems

Landfills across Indian cities lack proper segregation and scientific composting systems. As a result, anaerobic decomposition (in the absence of oxygen) dominates, producing large volumes of methane.

This contributes not just to global warming, but also to urban air pollution—already a public health crisis in India.

Food waste in India contributes significantly to methane emissions, further accelerating climate change.

Climate-Smart Solutions

By simply reducing avoidable food waste at the household, retail, and hospitality levels, India can significantly cut down its methane emissions.

Moreover, scaling up composting, biogas generation, and food redistribution programs can turn this environmental liability into a climate-smart opportunity.

According to the UN, tackling food waste globally could eliminate nearly 11% of all greenhouse gas emissions.

For India, with its dual challenge of food insecurity and environmental degradation, curbing food waste offers a powerful pathway toward sustainable development and climate resilience.

Harm to Biodiversity

India is home to some of the richest biodiversity in the world—from the Western Ghats and Himalayan forests to the Sundarbans and coral reefs.

But unsustainable agricultural practices, driven in part by food demand and food wastage, are steadily eroding this natural wealth.

The conversion of forests and grasslands into farmlands and livestock pastures is one of the most direct threats to biodiversity. As demand for dairy and meat products grows in urban India, more land is being cleared for livestock rearing.

This not only displaces native species but also fragments critical wildlife corridors—affecting tigers in Madhya Pradesh, elephants in Kerala, and countless other species across states.

Monocropping—the repeated cultivation of a single crop like rice, wheat, or sugarcane to maximize yield—is also widespread in India, especially in states like Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh.

While this boosts short-term production, it gradually weakens the soil, reduces pollinator populations (like bees), and increases dependency on chemical fertilizers and pesticides—all of which diminish biodiversity over time.

Threats to Marine Life and the Hidden Cost of Food Waste

India’s marine ecosystems are equally under stress. Overfishing in coastal regions such as Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh has led to a dramatic decline in fish stocks.

Trawling and by-catch practices (where fish not fit for market are discarded at sea) threaten marine food chains.

In some Indian waters, species like Indian mackerel and pomfret are being caught faster than they can reproduce.

When food is wasted, especially seafood and animal products, the environmental cost is doubled. Not only are natural ecosystems disrupted to produce that food, but all the energy, water, and life taken from the land and sea goes to waste.

This accelerates biodiversity loss and pushes fragile ecosystems closer to collapse.

Protecting India’s biodiversity requires more than just conservation laws. It demands rethinking how much food we produce, how we consume it, and how much of it we allow to go to waste.

Organizations tackling food waste in India are proving that redistributing surplus food can have a major impact

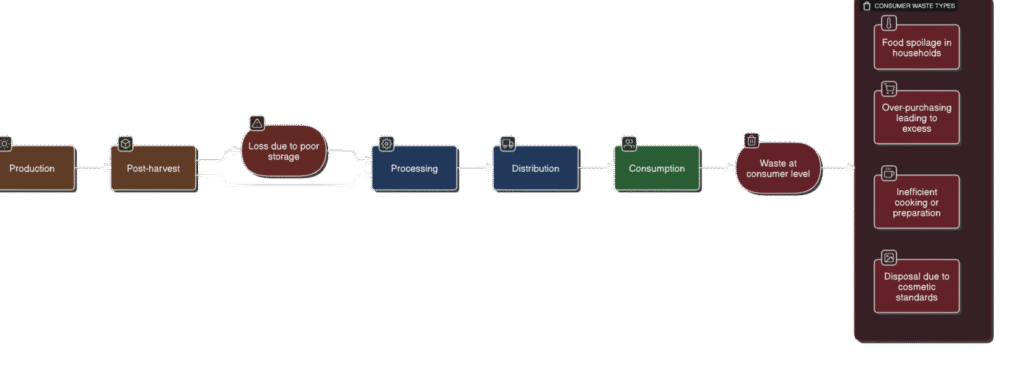

Stages of Food Loss and Food Waste in India

Food loss and food waste happen at different points along the supply chain—right from the farm to the dinner table. Understanding where and why food is lost or wasted helps us find better solutions to reduce it.

1. Food Loss: Early Stages

In India, most food loss happens before the food reaches shops or markets. This includes losses during:

- Harvesting – Crops are damaged by weather, pests, or delayed harvests.

- Storage – Grains spoil due to poor storage conditions, lack of temperature control, or pest attacks.

- Transport – Vegetables and fruits get crushed or rot during long journeys, often in non-refrigerated trucks.

- Handling – Farmers may not have access to proper tools or training for safe handling.

These problems are more common in rural areas, where farmers lack cold storage, packing facilities, and proper market access. For example, in India, nearly 30–40% of fruits and vegetables are lost post-harvest due to inefficient supply chains.

2. Food Waste: Later Stages

Food waste is more common at the retail and consumption stages—in stores, hotels, restaurants, and homes. This includes:

- Discarding edible food because it looks imperfect or doesn’t meet quality standards.

- Overproduction in hotels, weddings, and canteens where large quantities of food are cooked but not consumed.

- Throwing out food at home due to overbuying, improper storage, or confusion about expiry dates.

Urban households and businesses in India tend to waste more food at this stage. For instance, Indian metros like Delhi, Mumbai, and Bengaluru throw away over 20–25% of the food served at events and restaurants.

Why Later Food Waste Hurts More

The later food is wasted in the supply chain, the greater its environmental cost. That’s because more resources—water, fuel, labor, packaging, refrigeration, and transport—have already been used.

Imagine a plate of biryani thrown away in a hotel. It’s not just rice and meat being wasted, but all the land, water, electricity, and effort that went into preparing it.

Reducing food loss in the early stages and food waste in later stages requires different strategies, but both are equally important for building a sustainable and food-secure India.

Addressing Food Waste in India

Tackling food loss and waste is one of the most urgent steps India can take to fight hunger, protect the environment, and build a sustainable future.

Reducing food waste is directly linked to achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12.3, which calls for halving global food waste and reducing food losses by 2030.

To solve the problem of food waste in India, efforts must span from rural farms to urban homes

But this can’t be achieved by one group alone. Everyone—farmers, retailers, households, businesses, NGOs, and the government—has a role to play. Here’s how we can start making progress:

1. Policy and Government Action

India has taken early steps toward reducing food waste, but much more can be done. For example:

- The Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) launched the Save Food, Share Food, Share Joy initiative, encouraging safe food donation.

- Some states have introduced municipal bye-laws that support food donation and composting at the community level.

India can learn from global best practices too. France, for instance, made it illegal for supermarkets to throw away unsold edible food, instead requiring them to donate it. India could implement similar food redistribution policies at scale.

In the long run, India must develop a National Food Waste Reduction Strategy that includes targets, measurement tools, and clear guidelines for businesses and consumers.

2. Improving the Supply Chain

In rural India, food loss starts right at the farm. Investments are needed in:

- Cold storage to keep fruits and vegetables fresh after harvest.

- Better packaging and transport to reduce damage in transit.

- Agri-tech tools to help farmers track and preserve produce more efficiently.

Public-private partnerships can help create mini cold chains, local warehouses, and processing units to cut losses in tier-2 and tier-3 towns.

3. Food Recovery and Redistribution

NGOs and community kitchens are already leading efforts to rescue surplus food from weddings, restaurants, and corporate cafeterias. Reshine Organisation, for example, works on this model.

Scaling these efforts requires:

- Clear legal frameworks to encourage safe food donation.

- Partnerships with food businesses, such as hotels, supermarkets, and caterers.

- Public awareness about safe food handling and redistribution.

Redistributing just a fraction of wasted food could help feed millions of hungry Indians each day.

4. Consumer and Retail Behaviour

In urban areas, households and retailers contribute heavily to food waste. To change this:

- Consumers can be encouraged to plan meals, store food properly, and use leftovers.

- Supermarkets can stop rejecting fruits and vegetables that are imperfect in shape but perfectly edible.

- Restaurants and caterers can avoid overproduction and offer smaller portion sizes.

Simple actions like sharing leftovers, composting, and checking expiry dates more carefully can reduce household waste dramatically.

5. Recycling and Reuse

When food cannot be eaten, it can still be useful:

- Composting organic waste at home or in communities improves soil and reduces landfill burden.

- Feeding livestock with safe food scraps reduces costs and waste.

- Technologies like CHUGG in India turn food waste into biogas, a clean energy source.

These methods align with a circular economy approach, turning waste into value.

6. Data and Research

India currently lacks reliable, up-to-date data on food waste. To build effective policies, we need:

- Detailed tracking of food loss and waste across states and sectors.

- Research on the Water–Energy–Food Nexus, especially in drought-prone areas.

- Localized studies to understand how food waste affects nutrition, hunger, and climate change in India.

The FAO Food Loss and Waste Database allows researchers and policymakers to monitor food loss trends by product, stage, and region.

Conclusion: Combating Food Waste in India for a Sustainable Future

Food loss and waste are serious challenges that deeply affect both our environment and food security. When one-third of all food is wasted, we not only worsen hunger for millions but also waste huge amounts of water, land, energy, and fuel.

In India, where many people still face daily hunger, this issue is especially critical.

Wasted food that ends up in landfills releases methane, a powerful greenhouse gas that adds to climate change.

To fix this, we need action at every level of the food chain—from farms and factories to shops, homes, and policy makers.

We must invest in better storage, smarter supply chains, food donation systems, and public awareness. At the same time, strong data and research can help shape smart policies that protect both people and the planet.

Reducing food loss and waste is not just smart—it’s urgent, ethical, and essential for building a hunger-free, sustainable India.

“Reducing food waste is not just environmental. It’s ethical.”

– Reshine Organisation